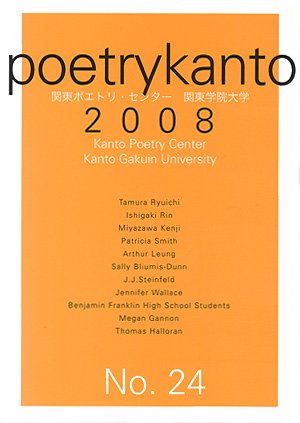

2008 issue

What if it’s true, that a life of poem-making–in allowing one to go deeper and deeper into the mix and in opening shared spaces–can be a life risking all? That a life approaching the condition of poetry or music risks being alive to the divine, to those elusive gods within and without that as primordial energies guide and give shape to human destiny (even while reminding us in various guises that a light touch about the seriousness of one’s work is always what’s most needed). For the poetic ambition may range–to cite American examples–from putting a human being freely, fully and truly on record (Walt Whitman), to converting one’s life into legend (Stanley Kunitz), to making a social place for the soul (Allen Ginsberg), to dying and being reborn more attuned to nature (Galway Kinnell), or simply to letting the voice of the soul be heard (Mary Oliver).

But beyond ambition lies responsibility. Poets are not only privileged as it were by the ‘gods’, they are charged by them with certain responsibilities. Words, and the way we care for them, love them, honor them, are the responsibility of all of us who most need them (Words, words–who needs words? I once heard a poet ask. Who doesn’t need words? came the reply–from another poet, naturally). For out of our words come our dreams–those fragile, gossamer connections to our deepest selves that show us at the seams/seems of reality how to live a life of ever-shifting imaginative depth.

Japan has a rich poetic culture stretching back centuries, and it has a growing number of contemporary poets who are being actively translated into English and other languages. Poetry Kanto would like to help empower a new generation of Japanese poets. As Walt Whitman once wrote: ‘I am enamored of growing out-doors.’ It’s time for countries like Japan to unleash, as it were, its ‘soft’ or cultural firepower, to unmuzzle those new and emerging voices who need to be heard “outdoors.” For the future–and we don’t necessarily advocate a “globalized” future in economic terms–the future, we feel, is deeply connected to what the East has to teach us in the realm of culture, especially poetry. Poetry can offer unique insights into human thought and consciousness that no other human activity–save for music or meditation–can offer. The living legend that is Tanikawa Shuntaro, who in his prolific and extraordinary career has raised the bar for the next generation (and well beyond) of poets of Japan, is currently unrivaled here in terms of cultural presence and poetic output. But of course there are other presences on the contemporary scene, glimpses of whom readers of Poetry Kanto over the years have been able to catch.

Even if one’s knowledge of a language were unlimited, it would be all too easy to say–as the truism goes–that poetry is what gets lost in translation. Make no mistake, however, what gets found in translation is the very stuff of poetry. It is the heart of the miracle of being human, we who as language-vehicles are “natural-born translators”. To be human means that our experience of the world must get translated into words, so that we may in turn humanly experience the world–go figure!

For this issue of Poetry Kanto we dip into the well– the commonwealth, if you will– of modern and contemporary Japanese poetries to bring our readers, among other exciting works, new translations by Princeton, New Jersey-based translator Takako Lento of the esteemed poet Tamura Ryuichi, whose lasting contribution– both as “Wasteland” founding member and as unparalleled inspiration to a generation or more of Japanese poets– the editors believe cannot be overvalued.

So in the following pages catch the new poetry wave advancing the poetic culture East, West, and beyond. For it is here, standing on the blood-soaked ground, eating the bitter-soaked bread of life, that we find our psyche-soaked words slowly coming alive.